There’s a photo of Sam Rivers (1923-2011) at the White House, most likely from the so-called “White House Jazz Festival” on the South Lawn during Jimmy Carter’s administration. “That blue suit he had on? He made that,” recalled Monique Rivers Williams, daughter of the revered multi-instrumentalist. “He sewed all his own clothes...he wasn’t just a musician.”

At the end of 2017, Verve Records unveiled Ella at Zardi’s, a previously unreleased live recording of an Ella Fitzgerald club date from February 1956. Excitement ran high over the album, believed to be Fitzgerald’s first live record ever. Until now.

First and foremost, Michael Janisch is a bassist. He’s about to drop his third solo album. He’s worked as a side player for dozens of A-list jazz artists. And he’s toured relentlessly with multiple bands. So, yes, a bassist first.

The legacies of our classic jazz singers, once considered popular singers, have considerable reach. These early adopters of the American Songbook still define how these works are performed, even as modern jazz singers shape traditional vocal jazz to their own inspired ends. For this months’ vocal jazz issue, let’s take a look at how the influence of some beloved musical forebears as yet moves through singers today.

Guitarist Ron Jackson plays with the sterling technique and measured swing of a Tal Farlow or Bucky Pizzarelli, but it would be a mistake to think of him as a strict jazz traditionalist. His new album, Standards and Other Songs, his ninth as a leader for his own Roni Music label, contains plenty of unexpected twists and outré moments, despite the title’s anodyne first impression.

Free jazz percussionist Andrew Cyrille introduced tenor player Kidd Jordan from behind the kit at Roulette on June 11, the opening night of the 2019 Vision Festival in Brooklyn, NY. “We’re going to take you someplace else,” he said before jumping into a mesmeric repartee with the saxophonist and monster improviser.

The reason that world-renown clarinetist Paquito D’Rivera likes playing with Mark Walker is that the multiple Grammy-winning drummer “doesn’t play too loud.” D’Rivera says this with a laugh, but he’s more than serious about his appreciation of the rhythmic refinement that Walker has brought to their 30 years of collaboration. “Many musicians, especially drummers, lose their energy when you ask them to play soft,” he explained. “Mark can play with the same energy without raising the volume. That’s really hard to find.”

June 1982 at The Hollywood Bowl. It was only the fourth year for the Playboy Jazz Festival at the celebrated amphitheater, and the lineup was spectacular: Freddie Hubbard, McCoy Tyner, Ron Carter, Tal Farlow, Dexter Gordon, Weather Report, The Manhattan Transfer, Grover Washington, Jr., Maynard Ferguson, Lionel Hampton, Dave Brubeck, Ornette Coleman, Willie Bobo, Woody Shaw, Milt Jackson, Sarah Vaughan. Front and center amidst this jazz royalty was vocalist Nancy Wilson, in a rare concert with trumpeter/ flugelhornist Art Farmer and saxophonist Benny Golson.

Violence. Brutality. Segregation. Exploitation. These are the words that singer/composer Sara Serpa uses when she talks about the family legacy that she inherited—a legacy that her latest musical projects tackle head on.

In 2016 Los Angeles-based vocalist Tierney Sutton and her eponymous band turned out a winning score for director Clint Eastwood’s film Scully. One of the tunes didn’t make the cut for the film but landed on the soundtrack; Sutton and co. reprise this uplifting song, “Arrow” on their latest release for BFM Jazz, Screenplay, a 15-song compilation culled from 80 years of Hollywood film-making.

On March 29, Blue Engine Records, the recording arm of Jazz at Lincoln Center, launched singer Betty Carter’s first posthumous album, The Music Never Stops (BE 0014; 1:16:05; HHHH). The album chronicles one of JALC’s early concerts—Carter in a whirlwind stage performance from 1992, on the same date as that of the release, backed alternately by a jazz orchestra, a string section, and three different piano trios. It’s Carter toward the end of her career, at her expressive and technical best.

Over the last decade, Tom Harrell has turned out about one HighNote album per year as a leader, trumpeter, and flugelhornist. A quintet of regular players usually serves as the core of these annual offerings, though not without deviations; sometimes he’ll double up his instruments, leave off a mainstay, like the piano, or add vocals or a guitar.

At times on Ancestral Recall (Ropeadope Records/Stretch Music), trumpeter Christian Scott aTunde Adjuah’s playing is so full of meaning that you can almost make out the intended words. He’ll repeat simple melodic phrases like a mantram over a rhythmic device culled from the African diaspora, then rise out of this polyrhythmic loam on a flying blast of sound. The view from above must be stunning.

Traditionally, and with clear exceptions, the success of a jazz performance depends on the three musicians at the fulcrum of the sound—the pianist, bassist, and drummer. Whether as a standalone group or a rhythm section for a larger band, this unit conveys the values that the composing mind holds dear.

There’s a lot to learn from San Francisco-based vocalist Mary Stallings. The nuanced phrasing. The unswerving feel. The emotional connection to the text. And that voice—as buttery as ever, 60 years into her career.

In May 2018 drummer Antonio Sánchez was performing with pianist/composer Arturo O’Farrill at the Fandango Fronterizo, a trans-border festival at the 18-foot-high fence that separates San Diego, California from Tijuana, Mexico. What impressed him was how people on both sides of the divide were singing and dancing together to son jarocho. For an instant the fence had disappeared.

The day before guitarist/composer Hedvig Mollestad Thomassen and her six-person band headlined at the 46th annual Vossa Jazz Festival (April 12-14), the group went hang-gliding in the mountains surrounding Voss, Norway. Voss, a small village on the train line between Bergen and Oslo, is a popular center for extreme sports—longboarding, dirt biking, BASE jumping—and the local delicacy is half a roasted sheep’s head, eye intact. Not a place for the faint of heart.

Linda May Han Oh has gotten used to carrying her double bass up the four flights of stairs to the Harlem walk-up that she shares with her husband, pianist Fabian Almazan. No doubt she’s had lots of practice of late.

In his intro to McCoy Tyner and Charles McPherson at 80, a tribute concert honoring these two jazz giants at Jazz at Lincoln Center’s Rose Theater April 5-6, saxophonist Sherman Irby summed up pianist/composer Tyner’s distinguished career in one sentence. “McCoy Tyner has presented the world with almost six decades of pure excellence,” he began.

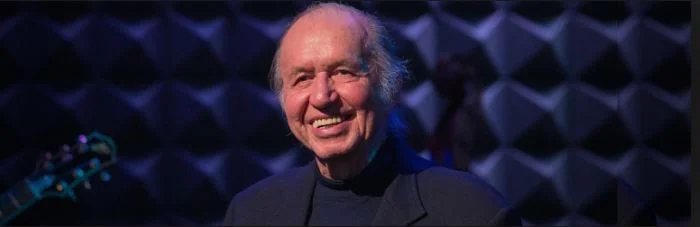

Singer/pianist Bob Dorough (1923 to 2018) is best known for his work as musical director and composer for the children’s TV show, Schoolhouse Rock!, which aired from 1973 to 1985. Under his direction, millions of children learned about conjunctions, the magic number three, how a law becomes a bill, and the preamble to the Constitution (my personal favorite). But few know that Dorough collaborated with many jazz greats like trumpeter Miles Davis, singer Blossom Dearie, and pianist composer Dave Frishberg, and that he recorded for various labels, even turning out three (magic) albums for Blue Note Records in the late 1990s.