Paul Jost had already enjoyed a successful, decades-long career as a drummer, sideman, and leader when he decided to work solely as a jazz vocalist. Switching from player to vocalist mid-course is not a typical career path for a musician. But Jost’s quick rise as a singer over the last six years—he sang at Dizzy’s Club Coca Cola for the first time just a few weeks ago—is a testament to his innate talent, his precision as a musician, and his distinctive vocal sound.

In truth, Jost has always had a good ear for vocals. Even though drums were his chosen instrument (he studied the same at Berklee College of Music), he would sing on gigs and compose for the voice. These occasional forays into vocalizing led to his work as a studio singer—and a prolific one at that. Jost, with a burnished vocal timbre that rock stars would envy, has sung on or composed hundreds of jingles and songs. (Jost’s “Book Faded Brown” is probably his most well-known tune, recorded by Carl Perkins in 1992 and Rick Danko and The Band in 1998.)

His unconventional path to singing gives him a 360-view of the art form. As musical director/drummer for venues like the Golden Nugget casino in Atlantic City and esteemed artists like singers Morgana King, Mark Murphy, and Billy Eckstine, guitarist Bucky Pizzarelli, and, most importantly, his friend pianist George Mesterhazy, he’s learned what works across a variety of musical settings. But it’s his innovative phrasing and expert sense of time as much as anything else that distinguish him as a jazz singer. He swings, but he also knows about pocket.

These skills in a vocalist make instrumentalists take notice. Vibraphonist Joe Locke, who’d heard about Jost from the singer’s usual rhythm section (pianist Jim Ridl, bassist Dean Johnson, and drummer Tim Horner), came out to hear him at a gig in Red Bank, N.J. Locke was impressed, and the two talked extensively afterwards. Finding that both were slated to play the 2018 Xerox International Rochester Jazz Festival in upstate New York (June 22-30), Locke invited Jost to join him on a few tunes. But as a lead-in to that gig, Locke asked, could Jost perform as a guest artist during Locke’s run at Dizzy’s in April? Jost agreed.

For the Lincoln Center gig, Jost learned about five compositions from Locke’s latest recording project, Subtle Disguise, among them the vibes player’s tribute to his creative mentor Bobby Hutcherson, “Make Me Feel Like It’s Raining.” Locke usually plays an instrumental version of the melancholic ballad, but for Jost’s guest turn at Dizzy’s he provided lyrics; the vocal version, renamed “A Little More Each Day,” was all the more poignant for Jost’s meaningful interpretation of Locke’s revelatory words. Equally moving was Jost’s pathos-soaked interpretation of Blind Willie Johnson’s, “Motherless Children,” a 1920s blues tune that takes on added meaning in a modern setting.

In Jost Locke finds a vocalist who brings as much passion to his singing as Locke does to his playing. The sympathetic understanding between the two musicians was most apparent on compositions where Jost used vocalese rather than lyrics to express a melody, instrumental line, or improvisation. For instance, on Locke’s “Red Cloud,” inspired by the Sioux leader of the same name, Jost created a magnetic solo punctuated with shouts and calls as an overlay to Locke’s rapid-fire mallet work. When it comes to vocal improv, it doesn’t get much better than this.

Locke also asked Jost to perform from his own repertoire; he chose “Blues on the Corner,” the McCoy Tyner composition that he recorded on his first solo jazz album, Breaking Through (Dot Time Records) in 2014, and two of his signature songs, “Caravan” and “If I Only Had A Brain.” These tunes—all of which showcase Jost’s effortless, impeccable scatting—benefit from his own whip-smart arrangements.

At the Rochester Jazz Fest on June 26 Jost and Locke will likely reprise several of the compositions they presented at Dizzy’s. But the day before, June 25, is Jost’s solo show with his own rhythm section and an opportunity for him to pull from any of his varied musical projects. Given the depth and breadth of Jost's range, the performance could contain anything from standards to vocal improv to spoken word to jazz covers of pop, rock, or country tunes—it's anyone's guess. Because aside from always-on performances, Jost is hardly a predictable singer.

Among Jost's more inventive (and ambitious) undertakings is his solo project, Born to Run Reimagined, a reworking of Bruce

Springsteen's breakaway hit album, Born to Run. In his jazz version, Jost keeps the identifiable musical bits from the original—no having to guess what the tune is—but his focus is on the poetry of Springsteen’s lyrics. “As an arranger, I want to have the freedom...to interpret things the way that I want, but I want to honor the music, too,” Jost says. “Normally I would just take a song and sing it a cappella and listen to what the words are trying to touch in me...and that starts to paint a picture. That’s what happened with the Springsteen music. He’s a wonderful lyricist.”

Like Springsteen, Jost has a natural rapport with an audience that at times seems more important than his considerable musical gifts. Perhaps it's his confidence with a tune, no matter whether he's playing or singing. Perhaps it's his ability to take much-beloved songs of almost any generation and make them sound new. Or perhaps it's the vulnerability that he brings not just to his performance but to his patter. “I want to connect—that's the main thing,” he says. “I want to strike that chord that touches all of us.”

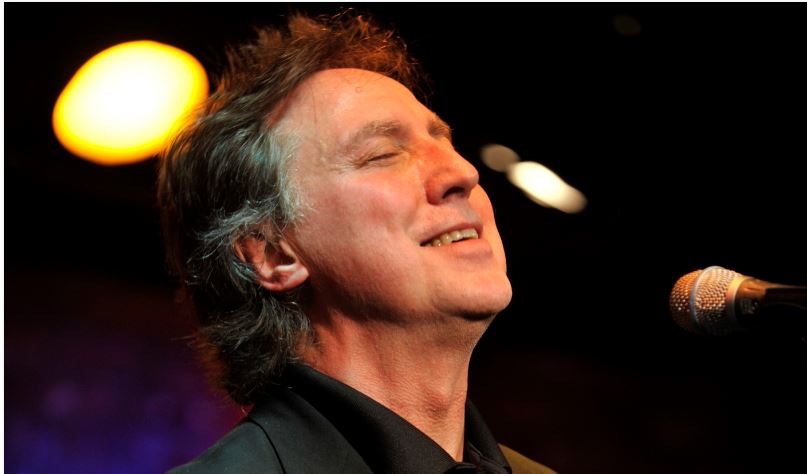

Photo: Jeffrey Apoian